| Lachie has made a table for the hut with a curved-end blackwood top, which is dowelled to eucalpyt legs (from an unknown street tree!). Dowelling replicates the mortise and tenon style of the pegged framing for the hut. The table is a beautiful piece of craftmanship and will serve us well on field days and events like picnic lunches in the clearing. Lachie has also carried out some basic maintenance such as oiling and re-liming under the eaves. He's pleasantly surprised at how well the liming has bonded with the wattle and daub, particularly given the perpetual wild wet weather we've endured this winter and spring. |

|

0 Comments

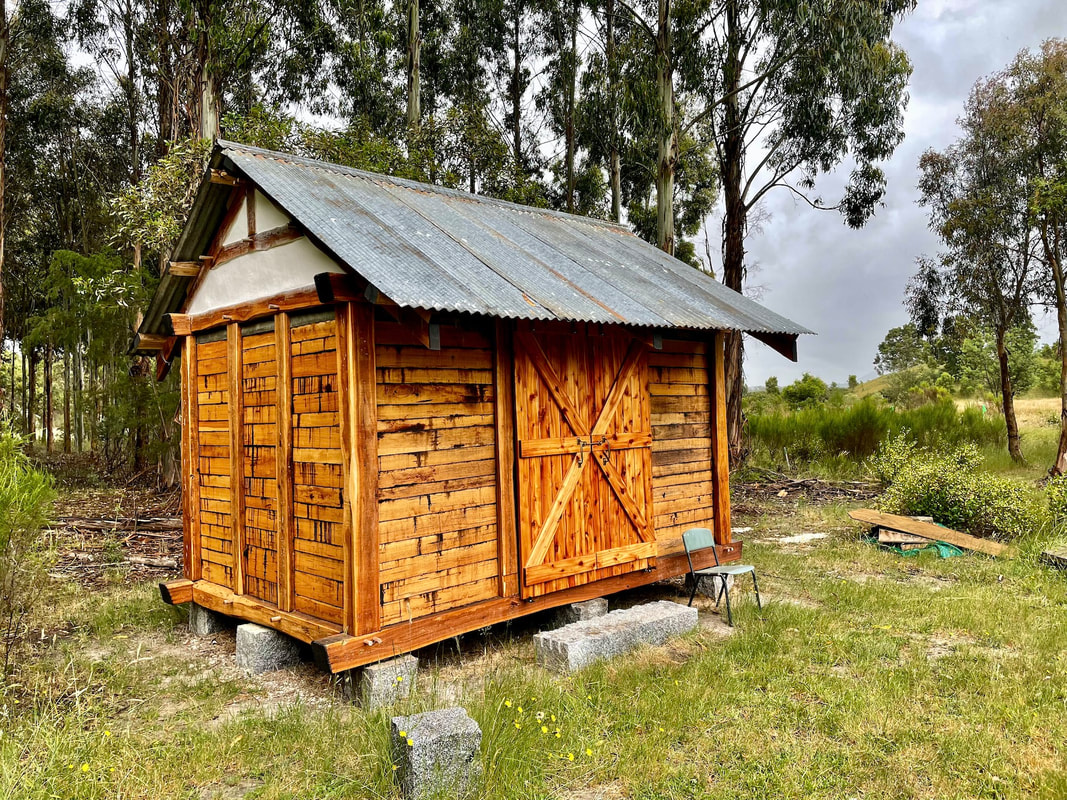

We had a dozen or so people come to the picnic lunch (really a sausage sizzle) on Sunday 10 April celebrating the drop slab hut’s completion. Gary and architect Geradine Maher were interviewed by freelance journo Genevieve Barlow.The weather was perfect and people seemed to enjoy themselves. A fitting end to the project

Lime render beneath the eaves and brass handles on the double doors were the final touches added by Lachie. Below is a gallery of images of the completed 21C drop slab hut.

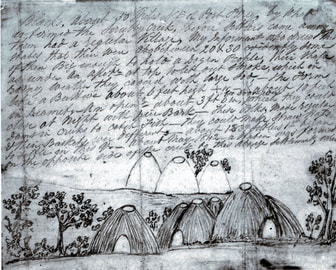

Indigenous village of domed huts, sketched SW Victoria, late 1830s. Indigenous village of domed huts, sketched SW Victoria, late 1830s. Wattle and daub the English call it, but we decided to draw on a cultural heritage that pre-dates our recent colonial layer. We’re going way back beyond the miner’s bark hut and the cattlemen’s drop slab hut. Back to the weatherproofing method applied for millennia to the sturdy beehive domes built by Indigenous people in what is now southwest Victoria. While the English brought the technique with them, let’s not give them the credit for its invention. Wattle and daub is simply ye old English for the stick and mud rendering used worldwide for filling the gaps in huts placed on plains and peaks wherever the weather was cold and wild, and the wind whistling through walls constituted an existential threat. Back in the motherland, the English wattle was a small flexible stick, often from a willow, cut green to ensure suppleness. In Australia, the word wattle became applied to the ideally suited, abundant Acacia species throughout our golden plains. To daub is to smear with mud or any soft, adhesive matter. Extra ingredients for ensuring a gluey mud mix consisted of grass for boosting structural strength and manure for added sticking power. So, in keeping with our place-based approach, Lachie and I looked around at what resources we had on-site within the biorich plantation. Swathes of young, invasive silver wattle sprouted within sight of the 21C drop slab hut’s clearing. For the sticky daub, Lachie pointed out we need look no further than the banks of the central dam, once a white clay kaolin quarry. Grass grew and kangaroo dung lay about – both in abundance. Through experiment, Lachie discovered how thin, straight wattle branches, with the knobs trimmed off, could be woven into a lattice at the gable ends, under the eaves. The thinner the better as they’re more flexible and allow a tighter weave. Clay and grass were trampled together with a generous dose of kangaroo dung. The resultant dark muddy mess had the consistency of play dough and was easily squeezed by hand throughout the lattice weave. As it dries, you can expect the daub to crack. For impenetrability and a smooth, flexible finish, Lachie applied a lime render, the formula for which is one part lime putty, three parts sand and chopped fine straw. The putty is made by soaking hydrated lime for 24 hours. Two coats of render were applied by trowel to the lightly dampened daub, then finished off with a lime putty wash, diluted to the consistency of milk and brushed on. In 1841, prior to settlement, Chief Aboriginal Protector, George Augustus Robinson, encountered a native village of 13 dome-shaped huts at Mt Napier made of arched tree limbs with small limbs, turf, grass and bark filling the intermediate spaces so it was proof against wind and rain. These were no flimsy mia-mias or humpies. He recorded they were “sufficiently strong for a man on horseback to ride over.” Other settlers in the southwest also noted seeing substantial huts over 2m in height and 3-5m wide – large enough to comfortably house a family. It would seem fitting that in this, the final step, we were able to hark back to a deeper cultural heritage than our immediate colonial past. Western civilisation, then and now, is hardly the apogee of sustainable ideals. We have much still to learn if we are ever – like the First Nations – to become custodians of the land to which we belong. For all ten Steps, visit – https://www.biorichplantations.com/blog/category/21c-drop-slab-hut The hut is now protected from winter winds and driving rain. Lachie has installed sliding double doors, a casement window and applied four protective coats of a natural oil.

The traditional board and batten barn-style doors are made strong and stable by holding them together with Z braces. Such bracing allows the use of thinner one inch black wattle boards, compared with the minimum two inch boards required for a solid door. Ease of access and aesthetics determined the installation of double doors. They’re hung with two and a half inch rollers on a steel rail. Another space and weight saver, and when they roll back, the view north across the clearing opens wide to a pleasing prospect. Also traditional in style, the four pane casement window has a black wattle frame within a messmate case and sill. Small panes make sense in spaces prone to damage by flying birds and falling branches. Brad nailed beading holds the glass panes in place, and it’s simple to lever off when a pane does need replacing. Brass butt hinges at the top allow the window to open up and out. Given it’s stronger than pine, the black wattle frame can be fined down to 32mm dimensions. When combined with the small panes, the whole has an elegant feel to it. The messmate case is similarly 32mm in dimension, with a thicker sturdy sill that slopes 15 degrees from inside to out, which takes moisture away. The doors, window and floor all received four coats of pure tung oil mixed 50/50 with white spirits for the first coat, then 60/40 for those following. Natural oils need a drying agent. While these are present in most modern oils you purchase, so are other additives. Tung oil resists water better than any other pure oil finish and does not darken noticeably with age. It is claimed to be less susceptible to mould than linseed oil. “If you want to be environmentally safe,” said Lachie, “stick to unprocessed plant-based products and add in the drying agent yourself, or use thin enough to allow for maximum penetration into the wood.” Simply apply by brush and rub off any excess after half an hour. Lachie did break his rule and apply one extra (processed) protective coat to the double doors. He argued apologetically: “I want to hold the red-orange lustre of the black wattle longer. I’ve applied a final coat of Osmo UV Clear to add an extra layer, slowing down the harsh northern aspect greying off the doors. “The can label claims that the product is ‘environmentally safe.’” For all nine Steps, visit – https://www.biorichplantations.com/blog/category/21c-drop-slab-hut  Brother Joe painting the drop slabs with bitumen tar as added weather protection. Brother Joe painting the drop slabs with bitumen tar as added weather protection. One of the hallmarks of modern Western culture is that we so often take the path of least resistance. We prioritise short term convenience over long term consequences. This, as we have already seen with black wattle (refer Step 5), can have perverse outcomes. Think too of plastic and how it’s overwhelming the oceans and marine birdlife. A supposedly ‘rubbish’ timber, Lachie has instead found that black wattle delivers superior quality floor boards. It’s far harder and denser than Baltic pine, which was brought over as ballast from Scandinavia in the gold rush era and was laid as flooring in Ballarat throughout the 19th century. It’s even harder and denser than mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans), which until the 1970s formed three-quarters of the new house frames and flooring in Victoria. Laying the black wattle floor boards in the 21C drop slab hut has gone smoothly. The stability of acacia compared with a eucalypt avoids tension and shrinkage problems. When Lucas sawmilled as green wood at 24mm, the black wattle was perfectly well-behaved, shaving down to a standard 19mm thick by 112mm wide board. Lachie chose to use a classic shiplap profile, where the rebate on opposite sides of the panel interlocks the boards as securely as tongue and groove. The boards were lain athwart chainsaw-milled messmate joists, 500mm thick by 150mm wide, which were set 450mm apart and notched into the bottom plate beam. Through-nailing was preferred by Lachie, as unlike trendy secret nailing, it allows the boards to be recycled. Secret nailing offers another example of Western culture’s myopic vision triumphing over what’s best for the planet. The wavy-red floor boards are yet to be sanded and oiled – the next step! In the meantime, Lachie has nailed a recycled corrugated iron roof above as protection from the weather. It was rerolled by an early 20th century tank iron rolling machine that was originally designed to put the curves into straight iron. Now deployed to bring back old distorted corrugated iron, the machine only works where the iron is malleable. Modern iron may look on the surface flashy, but it’s high tensile and – surprise, surprise – not recyclable. As well as being attached to the three pairs of pegged sugar gum rafters, the roof is supported horizontally by round bush poles. Skinny as they are, the bush poles serve as sturdy purlins that are fixed to the rafters with batten screws and twitched with tie wire at each end. Also sourced from sugar gum, the 100mm diameter bush poles are 12 year old thinnings hailing from the sugar gum plantation of Ballarat Region Treegrower (BRT) farm forester, Phil Kinghorn. Farm foresters are constantly attempting to dream up ways of making money from plantation thinnings. As a plantation grows, every second tree needs removing on a regular basis if the best formed and straightest tree trunks are to thicken up sufficiently for most timber uses. Skinny bush poles playing a support role in construction are one way to fill this gap. Minimally processed, the poles were chainsawed flat on top and bottom sides, otherwise retaining the outlines of their origins. “It makes for a pleasing organic contrast, I think,” said Lachie. When it comes to natural products, less can often mean more. # For all eight Steps, visit – https://www.biorichplantations.com/blog/category/21c-drop-slab-hut  In building a hut from green wood, drop slab walling – according to Lachie – delivers the most satisfying blend of benefits over other materials, such as weatherboards, vertical slabs or corrugated iron. The drop slabs for the walls of miners’ and cattlemen’s huts were traditionally riven lengthways from a messmate or mountain ash log using a broad splitting axe or wedges. Lachie’s 21st century refinement is to replace pure brawn and deploy what is known as the Alaskan chainsaw mill technique. Lachie began by felling a messmate in private native forest on top of the Dividing Range in central Victoria. Messmate (Eucalyptus obliqua) is the dominant species in the dense forests of the south-western Divide. It splits easily and was described by 1850s gold miner William Howitt as “the most useful of trees” for mine props and hut construction. A sturdy hardwood, messmate holds the honour of being the first tree to be encountered by a European explorer; namely, Dutchman Abel Tasman as he skirted the southern end of the island named after him in 1642. Lachie’s chosen messmate was tall and straight with little taper – ideal for cutting into uniformly thick slabs. Under the Alaskan innovation, an aluminium frame is fitted above the chainsaw bar. The rigid frame guides the chainsaw, ensuring it slides evenly as it cuts longitudinally through the log. This simple setup replicates in miniature a mobile sawmill. Such downscaling meant the tree fellers could sled with huskies into back country, find a towering conifer and fall and disassemble on the spot. To remove the first curved outside flitch, Lachie aligned a homemade rail/ladder along the centre of the log. This assures that the first longitudinal cut through the log follows the true plane between the pith or centre of the log at each end. Crude judgement of thickness by eye is abandoned. Prior to slicing off each quartersawn layer of 2” slabs, Lachie measured precisely at log ends. The consistency achieved rivalled a loaf of Tip Top.  Back in the ImLal clearing, the long slab lengths are transformed into drop slabs when cut into short lengths and slotted into place between the standing posts of the hut’s frame. Literally, they are dropped into place from the bottom plate beam upwards; one on top of each other, with gravity replacing the job of glue or mortar in binding the wall together. “It’s so simple and workable,” says Lachie. “The short horizontal lengths provide lateral strength without any fixing. Plus their small size makes them easier to handle and you avoid the shrinkage problems faced with vertical slabs.”  Besides cutting into lengths, the only other essential characteristic of a drop slab is to create a 30 degree bevel top and bottom. Flat in profile, slab edges sloping uphill prevent rainfall finding its way inside. Why, you may ask, do slabs need to be so thick? Two inches is enough to prevent distortion and, just as importantly, offers excellent insulating properties – almost the equivalent of a double brick wall.  Lachie sees no need to reinvent the drop slab wall. “What I love is that you’re making a whole wall from one piece of wood. As well as cladding, you’ve got a moisture barrier, weather seal, insulation and internal lining.” And in the hands of a craftsman, the drop slab wall is a work of art. What’s not to love?  Moorabool Landcare Network visits during their Xmas party. Moorabool Landcare Network visits during their Xmas party. Prefabricated off site, it took Lachie and a team of three little more than two hours to erect the sugar gum frame on site in the clearing at the Imal biorich plantation. While careful preliminary craftwork is essential to the traditional mortise and tenon building technique, prefabrication is becoming increasingly fashionable today. It allows for quality control and pre-packaging has enabled a faster roll-out of new houses to replace those lost in the Black Summer bushfires. The bottom plate beams for the 21C drop slab hut were laid out on a grid of ‘granite’ staddle stones. Bolts through the beams were nested into a central hole on top of each stone. Armed with a spirit level, Lachie adjusted the height of each bolt, until the base floated perfectly flat above the ground’s surface. The stones serve two obvious purposes and one not-so-obvious: they ensure underfloor air flow, stop termites and offer the clearance for lifting the hut and transporting it to another location. Like a jigsaw, the post and beam pieces slotted together. Unlike a jigsaw, Lachie had numbered each piece, so the team knew exactly where each piece was supposed to go. Corner posts were wrestled into place. Uprights for window and doors carried to their assigned slots. Then came the moment to bring out the modern machinery to do the heavy lifting of the top plates. Lachie had hired a Telehandler with a wide forklift for the day. Up and over went the long beams, with the team atop ladders gently guiding these nine metre-long heavyweights onto the post-top tenons. As each of the four sides was capped with a beam, pegs were hammered through the corner posts and beams, anchoring the 3D jigsaw into a fixed pattern. Finally, the Telehandler raised its articulated arms high and added the gabled framework for the roof. The oiled skeleton of the drop slab hut gleamed firm and proud, the solid wooden frame at one with its natural surrounds.  The high levels of tannin in black wattle makes the wood rich red in colour. A beautiful stable timber, it grows well in low rainfall, and was once widespread, thriving in the heavy clays of the basalt plain that extends from the outskirts of Melbourne to beyond the South Australian border. As a common local timber, we thought it was an ideal candidate for the flooring and window frames in the 21C drop slab hut. From settlement’s outset, however, black wattle (Acacia mearnsii) was consigned to a low value destiny – similar to sugar gum. With its bark found to contain 40 per cent water-soluble tannin, industry seized on it as ideal for cleaning and preserving animal skins. Countless numbers of black wattle were flayed alive, with their bark stripped and bundled up for making leather or scouring sheepskins in the cities’ tanneries. Sent overseas for its tannin qualities, black wattle soon developed a poor reputation. From South Africa to Germany, it became regarded as an invasive weed. Its tough black seeds readily germinate once damaged. After fire, it suckers prolifically creating dense thickets that eliminate other species. Around 15yo, the species becomes untidy, literally falling apart. Tainted by its past, the best that agroforestry manuals can recommend for black wattle is to plant it as a nurse crop for more valuable timber species. When grown in alternate rows, the fast growing black wattle forces the more favoured species of eucalypt or exotic timber to grow straight as they strive to reach the sun. After 5-10 years, the manuals recommend cutting out the black wattle for firewood. At his property near Mt Egerton, Ballarat Region Treegrower (BRT) farm forester, Campbell Mercer, put this formula into practice. In 2003, he planted a 20 acre woodlot of black wattle nursing a range of species from brown stringybark to cypress. Fifteen years on, the black wattle was outcompeting everything else on a wet, south-facing slope. Encouraged by BRT’s resident pruning fanatic, Phil Kinghorn, Campbell had over the years pruned some of the black wattle and he thought: “There must be a better use than firewood, particularly as some of the trunks are in excess of 20cm and clear to 10’.” Using Phil Kinghorn’s mobile Lucas Mill, they produced some 1” and 2” boards with ease. There was no shrinkage or end checking and the milled boards had a distinctive wavy grain pattern and swirls of dark red. They sent the boards to specialist timber retailer, Fairwood, in Melbourne for appraisal. Fairwood knew nothing about black wattle and were amazed at the colour and how it sustained such a good polish,” remarks Campbell. “Given it grows so strongly and has the added benefit of offering a dense and clean burn for any firewood thinnings, I don’t understand why it’s not a popular timber plantation species.

“Maybe it’s something to do with the tree being naturally very branchy, making it totally unsuitable for timber unless pruned.” Campbell and Phil went on to mill six cubic metres of 1”and 2” boards of black wattle. We are the first to buy the boards, with Lachie picking up 92 lineal metres on a fine day this spring. When he finishes them for flooring and frames, who knows what standard they might reach? We’ll keep you posted!  Traditionally, in Europe and North America the pegs for the holed post (mortise) and grooved beam (tenon) are made of oak. That’s the way it’s always been. In what is possibly a world first, Lachie decides to try shaving down some sugar gum offcuts. We are determined to use as many local materials as possible. What innovation ever occurred without taking a risk? Lloyds of London refused to insure the first Tasmanian clippers made of the only timber available to the local boat builders in the early 1800s – blue gum. One hundred years later they were still plying the Derwent. As a Class 1 naturally durable hardwood, we know that sugar gum will have more than sufficient strength to hold the hut’s frame together. The known unknown is whether or not the dense sugar gum will shave to a taper smoothly? Lachie starts roughing out the offcut’s taper with a small axe. The sugar gum offcut is clamped down to the neck of his home-made saw horse. He mounts and begins work stropping back and forth with his two handled shaving knife, whittling the pegs down to a point. “It's smooth as…,” Lachie declares. Lachie estimates that he will be able to produce the 50 or so pegs for holding the hut’s frame together in little more than a day astride what he fondly dubs his “pleasure pony.” |

AuthorGib Wettenhall is interested in how we carry out large scale landscape restoration that involves the people who live in those landscapes. That, he believes, would build truly resilient landscapes. Categories

All

|