What is a biorich plantation – planting for people and the planet

A forestry plot of Otway blue gum four and a half years after planting.

Integrated with other forms of vegetation, a ‘biorich plantation’ aims primarily at enriching wildlife habitat potential across rural landscapes, not just for a lifetime, but in perpetuity. Observed from nature, a biorich plantation responds sensitively to the landscape, keeping a ‘sense of place’ in mind in its design and selection of species. In order to optimise biodiversity over the long haul, a biorich plantation must have sufficient scale and the full suite of vegetation layers from herb to canopy. Scale, siting, structure and species richness together determine whether or not a biorich plantation will become a self-perpetuating sanctuary for wildlife.

As a secondary complementary aim, the biorich plantation sets out to bridge the gap between farm forestry and environmental plantings. When combined with either a farm forest, agroforest or a monoculture plantation, the differing vegetation forms create a larger refuge for fauna and flora. And when linked with remnant bush or riparian planting, carefully sited farm and biorich plantations could act as stepping stones offering safe havens and passage to birds and animals through landscapes.

Crucially, adding commercial plantings to bulk out a biorich plantation offers material resources and income diversification to the landholder. This enables not only landscape but landholder resilience.

For landholders, choosing to adopt the biorich plantation path would signify a willingness to live within the limits of the land we inhabit and in balance with the rhythms of the earth. Biorich plantations are a sub-set of 'analogue forestry' – see next section.

To see a copy of the text and illustrations on the display board at the ImLal Biorich Plantation site – click here

As a secondary complementary aim, the biorich plantation sets out to bridge the gap between farm forestry and environmental plantings. When combined with either a farm forest, agroforest or a monoculture plantation, the differing vegetation forms create a larger refuge for fauna and flora. And when linked with remnant bush or riparian planting, carefully sited farm and biorich plantations could act as stepping stones offering safe havens and passage to birds and animals through landscapes.

Crucially, adding commercial plantings to bulk out a biorich plantation offers material resources and income diversification to the landholder. This enables not only landscape but landholder resilience.

For landholders, choosing to adopt the biorich plantation path would signify a willingness to live within the limits of the land we inhabit and in balance with the rhythms of the earth. Biorich plantations are a sub-set of 'analogue forestry' – see next section.

To see a copy of the text and illustrations on the display board at the ImLal Biorich Plantation site – click here

Mimicking the original natural forest structure as the no. 1 design principle

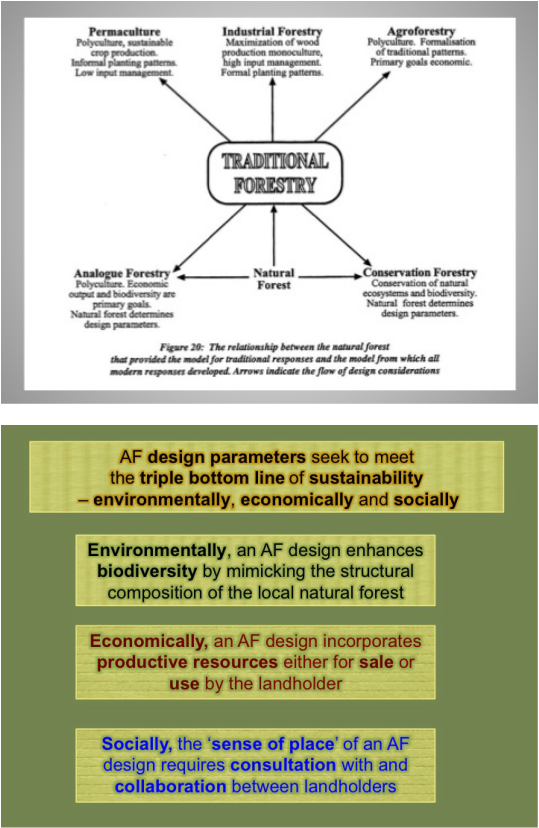

Almost 80% of Australia’s vegetation has been cleared, primarily for agriculture. Such large scale removal of the land’s protective cover and habitat for wildlife lies at the root of biodiversity decline and land degradation. To reverse this decline, planting trees on farms for both wildlife and for profit would seem the key to reconnecting fragmented rural landscapes. When combined, a biorich plantation and agroforestry approach form a vegetation cover system that is internationally known as an ‘analogue forest’ (see Figure 20).

Analogue forestry seeks to mimic and work with natural systems. In contrast to agroforestry and permaculture, an analogue forest design starts by researching, then copying the structure of the original native forest. As a secondary goal, an analogue forestry design involves consulting with landholders to develop some sort of commercial output that does not compromise the environmental restoration. Where exotic species are used, they should be analogous in ecological function and architectural structure to the original forest. This holistic approach aims to fulfil all three parts of the 'triple bottom line' of sustainability - see figure below and the conference paper on analogue forestry in Publications.

So, by intent and design, analogue forestry “attempts to create an economically productive and ecologically diverse tree-dominated landscape ‘analogous’ in structure and function to the nearest stable forest.” ( refer ‘Just like a forest,’ Down to Earth magazine, June 2011). The project described in this article has sought to diversify 23 monoculture tea plantations across a degraded Sri Lankan catchment with tree crops that have economic value, such as cinnamon, cloves and avocado. The riparian zones of gullies, which are the point of origin of many springs and streams, have been replanted, mimicking the species found in a small 14ha patch of native 'cloud' rainforest – the only climax cloud forest in the entire valley.

Three Australian Landcare representatives were in 2010 involved in launching Landcare in Sri Lanka. The Lanka Landcare Movement has used similar forestry principles to combine small kitchen gardens into larger forest garden sites in an approach they describe as 'regenerative agriculture.' A combination of shading from harsh tropical sunlight and increased leaf fall, which has enriched the unproductive sandy soils, has led to "phenomenal" outcomes in the village gardens (refer Lanka Landcare: a remarkable project by Victoria Mack, Sue Marriott and Matt Stephenson). In September 2011, Victoria Mack gave a detailed presentation to BRT on the work of International Landcare with our near neighbors – click here

A crucial aspect of this biorich-enhanced form of agroforestry is that it seeks to address both the cultural and genetic issues of biological loss. Thus, the cooperative involvement of community members is a fundamental aspect of their creation. This approach was also crucial to the development of the ImLal biorich plantation, which was based on cooperation between Imerys Minerals, the University of Ballarat, Central Highlands Water, the local shire, local citizens and landcare members.

Ballarat Region Treegrowers has joined the International Analog Forestry Network – for more information visit their website.

Analogue forestry seeks to mimic and work with natural systems. In contrast to agroforestry and permaculture, an analogue forest design starts by researching, then copying the structure of the original native forest. As a secondary goal, an analogue forestry design involves consulting with landholders to develop some sort of commercial output that does not compromise the environmental restoration. Where exotic species are used, they should be analogous in ecological function and architectural structure to the original forest. This holistic approach aims to fulfil all three parts of the 'triple bottom line' of sustainability - see figure below and the conference paper on analogue forestry in Publications.

So, by intent and design, analogue forestry “attempts to create an economically productive and ecologically diverse tree-dominated landscape ‘analogous’ in structure and function to the nearest stable forest.” ( refer ‘Just like a forest,’ Down to Earth magazine, June 2011). The project described in this article has sought to diversify 23 monoculture tea plantations across a degraded Sri Lankan catchment with tree crops that have economic value, such as cinnamon, cloves and avocado. The riparian zones of gullies, which are the point of origin of many springs and streams, have been replanted, mimicking the species found in a small 14ha patch of native 'cloud' rainforest – the only climax cloud forest in the entire valley.

Three Australian Landcare representatives were in 2010 involved in launching Landcare in Sri Lanka. The Lanka Landcare Movement has used similar forestry principles to combine small kitchen gardens into larger forest garden sites in an approach they describe as 'regenerative agriculture.' A combination of shading from harsh tropical sunlight and increased leaf fall, which has enriched the unproductive sandy soils, has led to "phenomenal" outcomes in the village gardens (refer Lanka Landcare: a remarkable project by Victoria Mack, Sue Marriott and Matt Stephenson). In September 2011, Victoria Mack gave a detailed presentation to BRT on the work of International Landcare with our near neighbors – click here

A crucial aspect of this biorich-enhanced form of agroforestry is that it seeks to address both the cultural and genetic issues of biological loss. Thus, the cooperative involvement of community members is a fundamental aspect of their creation. This approach was also crucial to the development of the ImLal biorich plantation, which was based on cooperation between Imerys Minerals, the University of Ballarat, Central Highlands Water, the local shire, local citizens and landcare members.

Ballarat Region Treegrowers has joined the International Analog Forestry Network – for more information visit their website.

How large and what shape?

A wide indigenous planting along a gully at Jigsaw Farms, WD Vic, inc paddock trees. It connects with a spotted gum plantation.

Studies of remnant vegetation patches on farms have found that 10ha is a critical minimum size for supporting a variety of forest and woodland birds. Plantations of this size are more likely to provide the food and shelter, and have sufficient genetic diversity, to maintain large populations of both plants and animals.

Traditional shelterbelts or smaller plantations are all 'edge effected', having no quiet or sheltered zone and they act as predator traps. Edge-loving birds are often the same gregarious species that we see in suburban gardens, but many other small and shyer birds will not live in such exposed situations.

Biorich plantations that are square will have a minimised ‘edge to area ratio’. The density of the boundary planting could play a critical role in determining if there is some quiet protected habitat within the plantation. Farm forests and biorich plantations could be used to extend the area of existing shelterbelts and remnant bush to the desirable size.

Traditional shelterbelts or smaller plantations are all 'edge effected', having no quiet or sheltered zone and they act as predator traps. Edge-loving birds are often the same gregarious species that we see in suburban gardens, but many other small and shyer birds will not live in such exposed situations.

Biorich plantations that are square will have a minimised ‘edge to area ratio’. The density of the boundary planting could play a critical role in determining if there is some quiet protected habitat within the plantation. Farm forests and biorich plantations could be used to extend the area of existing shelterbelts and remnant bush to the desirable size.