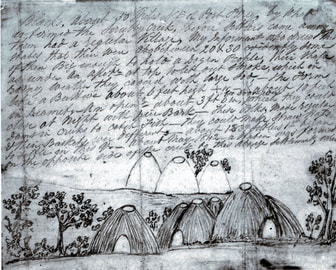

Indigenous village of domed huts, sketched SW Victoria, late 1830s.

Indigenous village of domed huts, sketched SW Victoria, late 1830s. While the English brought the technique with them, let’s not give them the credit for its invention. Wattle and daub is simply ye old English for the stick and mud rendering used worldwide for filling the gaps in huts placed on plains and peaks wherever the weather was cold and wild, and the wind whistling through walls constituted an existential threat.

Back in the motherland, the English wattle was a small flexible stick, often from a willow, cut green to ensure suppleness. In Australia, the word wattle became applied to the ideally suited, abundant Acacia species throughout our golden plains. To daub is to smear with mud or any soft, adhesive matter. Extra ingredients for ensuring a gluey mud mix consisted of grass for boosting structural strength and manure for added sticking power.

So, in keeping with our place-based approach, Lachie and I looked around at what resources we had on-site within the biorich plantation. Swathes of young, invasive silver wattle sprouted within sight of the 21C drop slab hut’s clearing. For the sticky daub, Lachie pointed out we need look no further than the banks of the central dam, once a white clay kaolin quarry. Grass grew and kangaroo dung lay about – both in abundance.

Through experiment, Lachie discovered how thin, straight wattle branches, with the knobs trimmed off, could be woven into a lattice at the gable ends, under the eaves. The thinner the better as they’re more flexible and allow a tighter weave.

Clay and grass were trampled together with a generous dose of kangaroo dung. The resultant dark muddy mess had the consistency of play dough and was easily squeezed by hand throughout the lattice weave. As it dries, you can expect the daub to crack. For impenetrability and a smooth, flexible finish, Lachie applied a lime render, the formula for which is one part lime putty, three parts sand and chopped fine straw. The putty is made by soaking hydrated lime for 24 hours. Two coats of render were applied by trowel to the lightly dampened daub, then finished off with a lime putty wash, diluted to the consistency of milk and brushed on.

In 1841, prior to settlement, Chief Aboriginal Protector, George Augustus Robinson, encountered a native village of 13 dome-shaped huts at Mt Napier made of arched tree limbs with small limbs, turf, grass and bark filling the intermediate spaces so it was proof against wind and rain. These were no flimsy mia-mias or humpies. He recorded they were “sufficiently strong for a man on horseback to ride over.” Other settlers in the southwest also noted seeing substantial huts over 2m in height and 3-5m wide – large enough to comfortably house a family.

It would seem fitting that in this, the final step, we were able to hark back to a deeper cultural heritage than our immediate colonial past. Western civilisation, then and now, is hardly the apogee of sustainable ideals. We have much still to learn if we are ever – like the First Nations – to become custodians of the land to which we belong.

For all ten Steps, visit – https://www.biorichplantations.com/blog/category/21c-drop-slab-hut